Product guy who does research from time to time

Translated by Lani Oh (elcreto)

*This article was co-authored by Xangle and DeSpread to promote understanding of the controversy surrounding the security status of staking and related assets.

Content

Staking: In the Crosshairs

Gary Gensler’s Snipe at Staking

SEC and Staking: How Far Will They Go?

Part 1. Determining the Security Status of Staking

Securities Laws, the SEC, and the Howey Test

Why Staking and Staked Assets May Constitute Investment Contracts

Why It May Not Constitute an Investment Contract Nonetheless

Part 2. Security Status of Staking Services

Types of Staking Service & Security Classification

Other Factors: Tokens, Protocols, Decentralization, Transparency, and Non-Custodial Nature

Closing Thoughts: Barrage of Regulations Clouding the Outlook for Crypto

An In-depth Look at the Regulatory Landscape of Staking

Domestic Implications; Uncertainty Nearing Its End

Staking: In the Crosshairs

Gary Gensler’s Snipe at Staking.

"The investing public is investing anticipating a return, anticipating something on these tokens, whether they’re proof-of-stake tokens, where they’re also looking to get returns on those proof-of-stake tokens and getting 2%, 4%, 18% returns.”

- Gary Gensler, speaking to the press on March 15, 2023

On March 15, Gary Gensler, chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), voiced his opinion during a meeting with reporters that all tokens with Proof-of-Stake and staking consensus mechanisms are securities and should therefore be subject to SEC oversight. It is significant that the SEC, which is already in the process of expanding its purview over a number of projects, is now recognizing that security status may apply even to the protocol level of staking.

Source: Staking-as-a-Service | Office Hours with Gary Gensler | U.S. SEC Youtube Channel

Especially since the Proof of Stake consensus algorithm is becoming the de facto standard for blockchain consensus algorithms after Ethereum’s Merge, a determination that staking activities are securities will beget various regulatory obligations on many blockchain projects. Once again, after the ICO regulations, regulatory uncertainty has loomed over the cryptocurrency market.

SEC and Staking: How Far Will They Go?

To clear up this uncertainty, Xangle and DeSpread teamed up for this joint research to understand the security status of staking within the validator-network relationship, which forms the essence of the asset's existence, and to speculate on how the SEC's upcoming regulatory actions would proceed. In this report, we'll take a look at 1) securities laws, the SEC, and the Howey Test, 2) pros and cons surrounding security classification of staking, and 3) potential implications of security status on staking-as-a-service, such as liquid staking.

Part 1. Determining the Security Status of Staking

Before we dive right in, let's briefly go over the background and purposes of securities laws, the SEC, and the Howey Test, which constitute the matrix of the security classification.

Securities Laws, the SEC, and the Howey Test

Background of the SEC

The SEC is a U.S. financial regulatory agency created to protect investors under the Securities Exchange Act. Back in the day, before the SEC came into the picture, investors were left to the mercy of Blue Sky Laws *, leaving them wide open to all sorts of fraudulent and manipulative tactics. In October 1929, a market bubble swollen by rampant leverage and fraud burst on "Black Thursday," wiping out fortunes from investors and plunging the U.S. economy into the depths of the Great Depression.

As part of the New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the SEC in 1934 to restore investor confidence. Charged with enforcing federal securities laws and protecting investors from fraud and other forms of financial misconduct, the SEC has become one of the world's most important financial regulators, with broad responsibilities that include overseeing stock exchanges, establishing disclosure standards, regulating broker-dealers and investment advisers, and enforcing corporate accounting standards.

* Blue Sky Laws: Prior to Black Thursday, there were state-level securities regulations, known as Blue Sky Laws (so named because some investment contracts were said to have "no more substance than so many feet of blue sky."). The rules not only varied from state to state but were limited in scope and lacked enforcement authority, rendering them virtually non-existent.

The Core Framework to Determine Security Status: The Howey Test

The SEC's ability to bring lawsuits, subpoenas, and enforcement actions against financial misconduct gives it tremendous powers as a financial watchdog and enforcement agency. The agency needed standards specifically to determine the traits that constitute securities in order to define the scope of its enforcement jurisdiction.

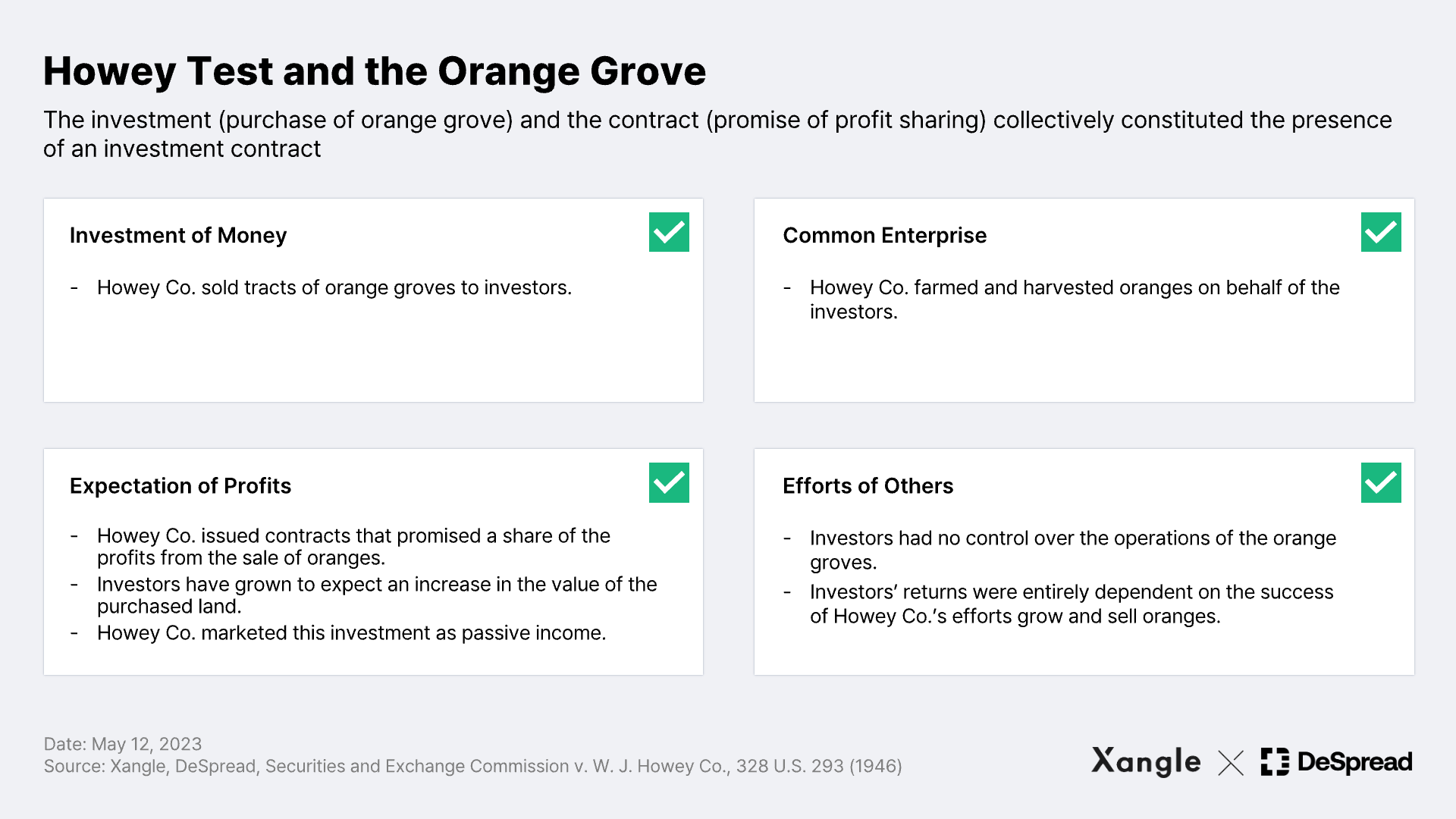

The security definition is based on the Securities Act of 1933. Types of securities include stocks, bonds, ETFs, options, and even investment contracts, which is currently one of the hottest topics in the cryptocurrency market. Investment contracts encompass all types of contractual arrangements wherein an investment scheme is involved, and are defined as an “investment of money in a common enterprise with a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the efforts of others." This definition was later established in Supreme Court precedents along with SEC v. Howey (1946)* and SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. (1948)*, and became the basis for the Howey Test, which remains the overarching standards for determining an investment contract.

The Howey Test is a framework for determining whether an investment contract exists in a particular transaction and consists of four elements, all of which must be satisfied in order to pass the Howey Test and be considered an investment contract.

Here’s the example of an investment contract cited in the SEC v. W. J. Howey Co. (1948) case*, which later established the Howey Test. The coexistence of an investment (the purchase of an orange grove) and a contract (a promise to share the profits from the orange grove) created an investment contract, which served as grounds for the SEC to sue W. J. Howey Co. for the sale of unregistered securities.

*SEC v. Howey: "In other words, an investment contract for purposes of the Securities Act means a contract, transaction or scheme whereby a person invests his money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party, it being immaterial whether the shares in the enterprise are evidenced by formal certificates or by nominal interests in the physical assets employed in the enterprise.”

The Howey Test and Crypto

The Howey Test carries significant implications for the crypto space, where the line between securities and non-securities can be blurred. If a particular asset passes the Howey Test, cryptocurrencies that have similar arrangements may inevitably come under the regulatory purview of the SEC. This is why the SEC has been suing several companies and projects in recent years. The strategy is referred to as Regulation By Enforcement*, whereby the SEC establishes precedent and builds the basis for regulation.

*"Regulation By Enforcement” typically involves establishment or clarification of rules and standards of conduct in a specific industry or regulated area through enforcement actions. One of the most illustrative recent examples is the SEC’s classification of ICOs as securities, which doused the ICO boom of 2017-2018. During this time, numerous companies raised funds by minting and selling digital tokens, yet almost none registered them as securities or complied with laws, rendering the market prone to financial frauds. The SEC brought enforcement actions against some of these companies and successfully classified tokens issued through ICOs as a form of security.

Why Staking and Staked Assets May Constitute Investment Contracts

The definition of a security is intentionally broad

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall once said that the Securities Act of 1933 defines the term security in sufficiently broad and general terms to achieve its goal of protecting investors. This is especially relevant in the crypto market, where the line between securities and non-securities is blurry, especially for the much-debated staking assets. Staking assets do not fit within any of the conventional categories of securities, i.e., stocks, bonds, ETFs, and options, and therefore may be subject to the Howey test to discern if the asset qualifies as an investment contract. In light of the recent investor harm associated with cryptocurrencies, a flexible definition of securities is interpreted as a commitment to bringing problematic crypto assets under the SEC's purview to better protect retail investors*.

*Retail Investor (Non-sophisticated Investor): U.S. securities laws divide investors into three categories based on their financial capabilities and access to information: Accredited Investors, who are classified as insiders or investors with sufficient assets, Sophisticated Investors, who demonstrate sufficient financial knowledge, and Non-sophisticated Investors, who refer to a broad range of general investors. To prevent fraudulent activities and potential harm, the SEC defines assets or products as securities and seeks to address the concentration of information and protect investors from losses within its regulatory jurisdiction through, for instance, disclosure platforms like EDGAR.

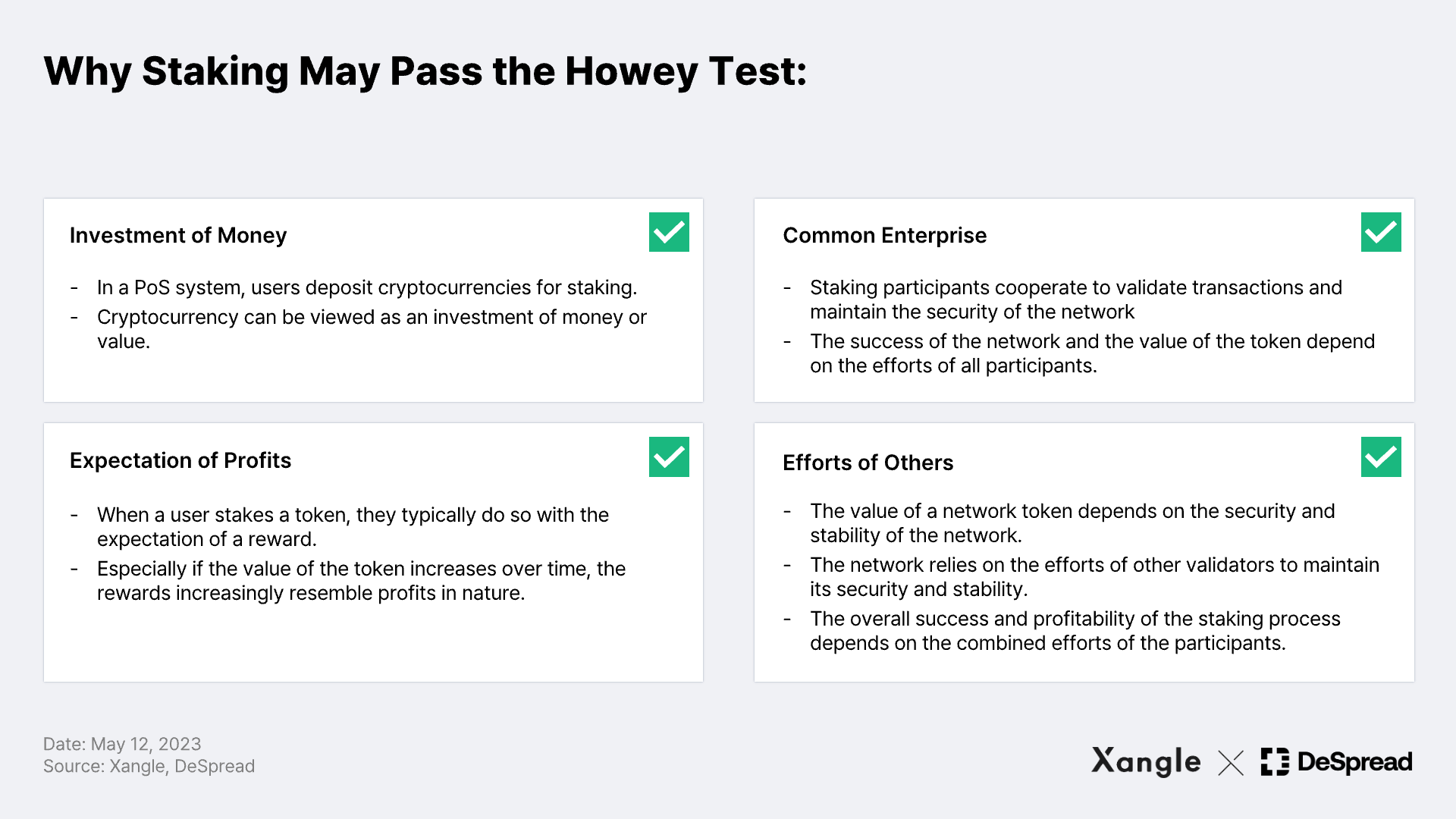

Staking: If It Passes the Howey Test

Now let's talk about why a native token on a PoS blockchain network might pass the Howey Test. Here’s how staking can tick off all four prongs of the Howey Test:

Put simply, the idea is that the validator nodes that form a consensus in a PoS network and the foundation that helps build the network's infrastructure are engaged in a common enterprise, and the investment is made with the expectation of profit from this business, which is attributable to the efforts of the foundation and the nodes.

Original Sin Theory & Embodiment Theory

Besides the Howey Test, the SEC has recently introduced two additional theories to determine the security status of cryptocurrencies, i.e., Ripple and $LBRY: the Original Sin Theory and the Embodiment Theory. Since staking assets are also defined as crypto assets used in the act of staking, these two theories, warrant a look alongside the aforementioned Howey Test.

The original sin theory in crypto reflects the view that a crypto asset sold through an investment contract will always be deemed a security. This classification extends to all future transactions involving the asset, regardless of any circumstances or future developments. This approach allows the SEC to firmly establish an asset's security status based on how the asset was initially distributed.

The embodiment theory serves as a complement to the original sin theory. According to the embodiment theory, if the circumstances and expectations that led to an asset's classification as a security continue to exist, the asset serves to embody what can be expected from an investment in that security. This takes into account the evolving nature of crypto assets and presumes that an asset is a security if the nature of the investment inherent in the asset—the facts, circumstances, promises, and expectations at the time it was classified as a security—remains unchanged.

The SEC has taken a comprehensive approach using these two theories to effectively address the multifaceted nature of cryptocurrencies and related investment contracts, and they have been instrumental in supporting the SEC's reasoning in the high-profile SEC v. Ripple Labs Inc* court case. Based on these two theories, various factors, such as how a cryptocurrency is initially distributed and how decentralized it is, may become more important than the act of staking in the crypto security debate. (Further exploration of the security aspects associated with various staking methods will be covered in a dedicated section below).

This view puts the SEC's current position that most cryptocurrencies including staking are securities into a better perspective. In a House hearing on April 19, 2023, SEC Chair Gensler appeared to take a broader definition of an investment contract, citing Justice Marshall:

"Congress’s purpose in enacting the securities laws was to regulate investments, in whatever form they are made and by whatever name they are called.”

*Ripple v. SEC: In the long-running legal dispute between the SEC and Ripple Labs, the SEC's claims under each theory were as follows:

- Original Sin Theory: The SEC argued that XRP should be considered a security because it was initially sold through an unregistered investment contract, and therefore all subsequent transactions involving XRP should be treated as securities transactions.

- Embodiment Theory: The SEC alleged that Ripple Labs promoted XRP as an investment opportunity, creating an expectation of profit. This argument is based on the logic that Ripple Labs' efforts to grow the XRP ecosystem would lead to an increase in the value of the asset. As a result, the asset XRP embodies the promises, expectations, and circumstances associated with the investment contract promoted by Ripple Labs to investors.

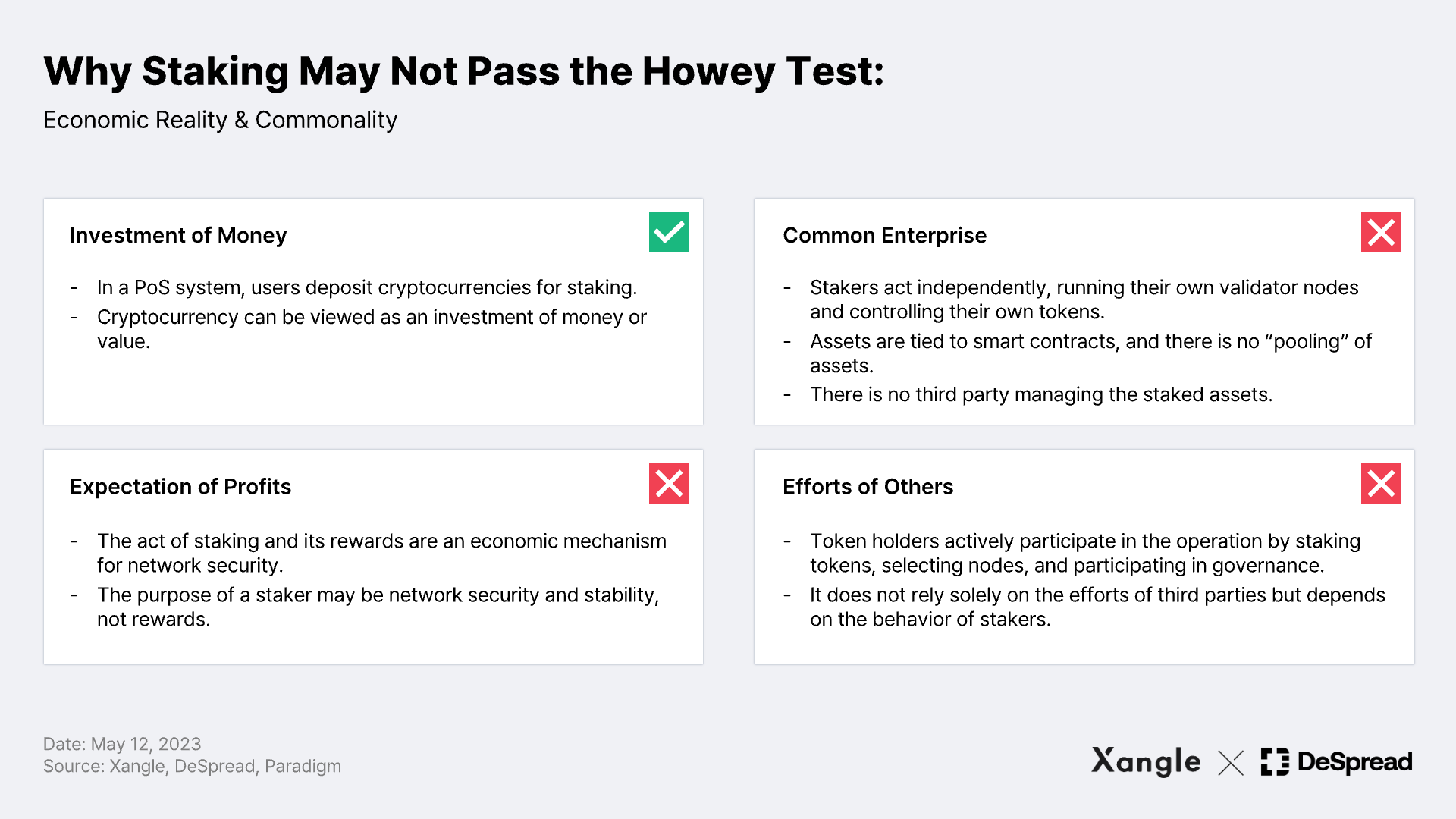

Why It May Not Constitute an Investment Contract Nonetheless

Of course, there is a counter-argument. At the heart of this argument is the notion of commonality, which is the basis for the formation of a common enterprise of the Howey Test, and the notion of economic reality, which is the focus on the actual economic arrangements rather than legal classifications in determining securities. So first, here’s a brief overview of these two concepts.

Horizontal and Vertical Commonality

Commonality is a key determinant of the forming of a group with shared interests in the Howey Test that necessitates identification of the promoter to discern the existence of a common enterprise. Depending on the interests and dependencies between the investor and the promoter, commonality can be divided into horizontal and vertical commonality. Generally, the presence of either of them is deemed to establish commonality*.

Horizontal commonality examines the existence of a common enterprise by assessing "horizontal relationship" between investors. This relationship is characterized by the pooling of assets and the distribution of profits based on the efforts of the promoter, thereby linking the individual investor's wealth to that of others. On the other hand, Vertical commonality emphasizes the "vertical relationship" in which a promoter is involved in a common business, and investors significantly rely on the promoter's efforts to pursue their interests. Essentially, establishing commonality relies on the presence of a structure, whether it be horizontal or vertical, through which investors receive profits driven by promoters.

*The commonality standards may vary among courts, but meeting either of these two commonality notions can be a prerequisite for passing the Howey Test: While Salcer v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. 682 F.2d 459 (3rd Cir. 1982); and Milnarik v. M.S. Commodities, Inc. 457 F.2d 274 (7th Cir. 1972) put more weight on horizontal commonality, Mechigian v. Art Capital Corp, 612 F. Supp. 1421, 1427 (S.D.N.Y. 1985); and Dooner v. NMI Limited, 725 F. Supp. 153, 159 (S.D.N.Y. 1989) placed more emphasis on vertical commonality.

Does Staking Establish Commonality?

In a proof-of-stake network, stakers (investors) lock tokens into a staking contract as a means of securing the network and maintaining consensus. But there is no entity that manages the deposited tokens, and the tokens deposited by a staker are not tied to the property of any other staker—hence, no investor-promoter relationship. Each staker is individually responsible for operating their nodes, and cannot expect to receive a profit proportional to the revenue generated by the promoter. They may even lose money if the node is operated inefficiently or exposed to slashing. That is, the absence of a structure where investors share profits with the promoter in staking remains a challenge in establishing commonality.

In this case, each staker earns profit based on their individual efforts, e.g., maintaining uptime and verifying transactions and compete* with others to generate blocks, which is more of a competition than a collaboration. There is no horizontal commonality, as staking basically isn’t a process where stakeholders share profits with each other.

Economic Reality

The other notion that warrants attention is the economic reality that underlies the act of staking. The concept of economic reality prioritizes the actual economic relationship involved in the use of a good or asset over its legal classification. According to this concept, a good that resembles a security in terms of its legal classification in the course of its use, operation and distribution is not a security if the purpose of its use is fundamentally different from the relationship between the investor and the promoter. A case in point is United Housing Foundation, Inc. v. Forman (1975). Back then, the Supreme Court held that stocks of Co-op City, a New York City co-operative housing corporation, were not securities due to the primary purpose of purchasing the stock being the right to occupy a home rather than investment in a profit-seeking business.

*United Housing Foundation, Inc. v. Forman (1975): The Co-op City Housing Project was a large-scale development intended to provide affordable housing for middle-class families. The project was organized as a co-operative, and each purchaser was required to purchase shares in the United Housing Foundation, Inc (UHF). The shares were not traded on an exchange and did not increase in value. Instead, the share price was directly tied to the price of the apartment, and owning a share gave the right to occupy a home in the co-operative. As such, some purchasers of shares in the Co-op City project filed suit against UHF, arguing that the shares were securities and therefore entitled to certain legal protections and remedies.

The Supreme Court, however, applied the concept of economic reality and focused on the intrinsic nature of the transaction rather than its form. It ruled that the shares were not securities, noting that they were not an investment in a profit-making business and that the primary purpose of purchasing the shares was to obtain the right to occupy the house. The court emphasized that the shareholders did not expect a profit from their investment and that the economic relationship between the shareholders and the co-operative was fundamentally different from the traditional relationship between investors and promoters. The rationale was that the focus of co-operative shareholders was the ongoing operation and maintenance of the housing project, not the pursuit of profit.

Staking in the Context of the Howey Test

Below is an overview that sums up the reasons staking on a PoS network does not constitute an investment contract based on the concepts of horizontal and vertical commonality and economic reality.

Security Status of Ethereum Staking

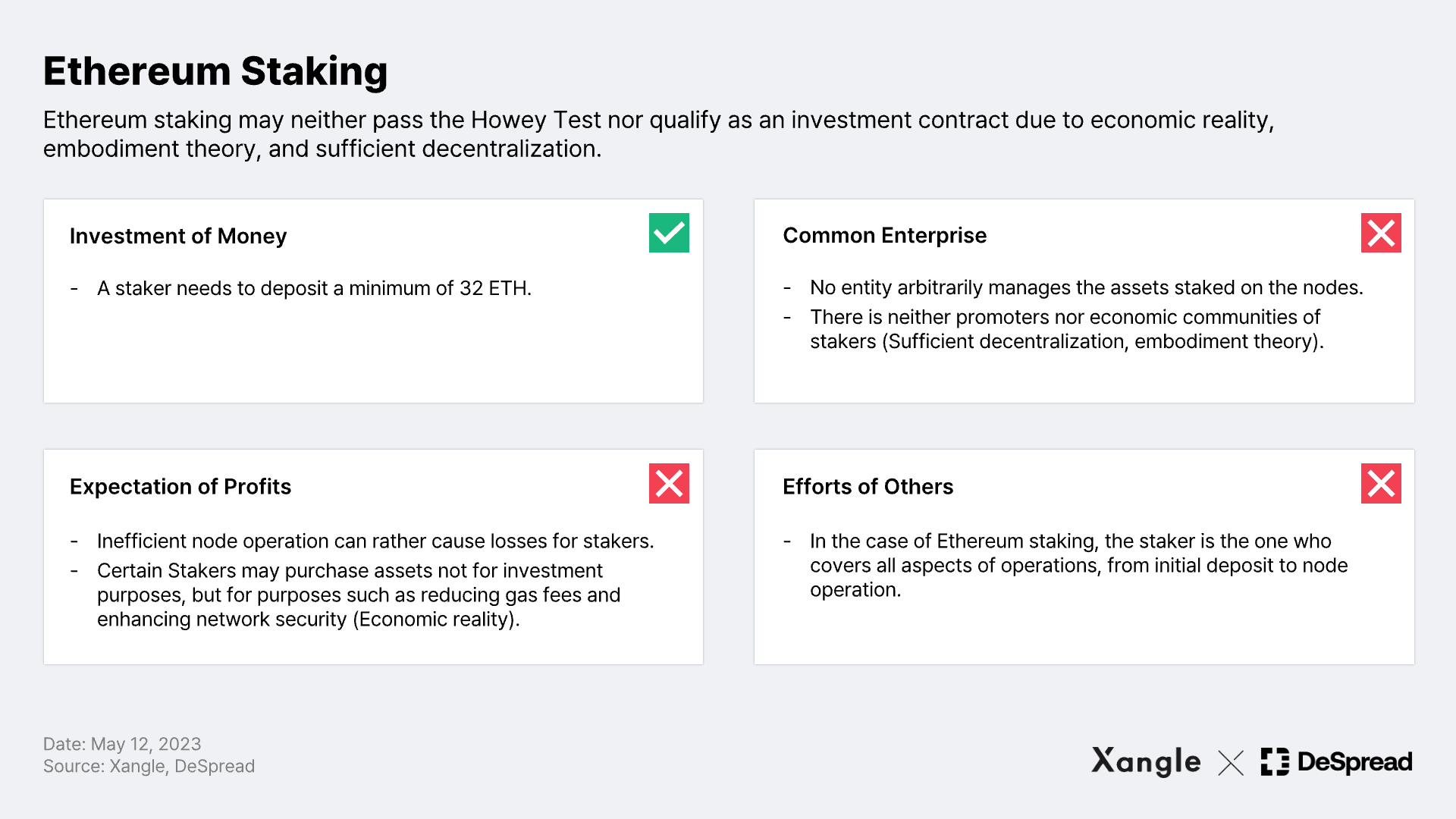

This section will explore if Ethereum staking qualifies as an investment contract based on the Howey Test:

As apparent in the example above, the security classification of staking loses ground when it comes to solo staking on the Ethereum network. This is because solo staking is performed by an independent individual, from fundraising to operation. Hence, there is neither common business nor other person's efforts, negating the applicability of investment contract.

Original Sin Theory and Decentralization

Some have argued that the Ethereum presale gives ETH the status of a security. This argument is consistent with the SEC's original sin theory. But at the same time, the SEC's embodiment theory can also be cited to prove ETH's non-security status. If the promise (contract) did not exist at the time of the pre-sale, then ETH would not be a security. This is where the concept of Sufficient Decentralization comes into play.

In a 2018 speech, William Hinman, former director of the SEC's Division of Corporation Finance, noted the decentralized nature of Ethereum, stating that "based on my understanding of the present state of Ether, the Ethereum network and its decentralized structure, current offers and sales of Ether are not securities transactions.”

His logic is that a sufficiently decentralized network where buyers of a token have no expectation of the efforts of others negates the presence of investment contract. He directly referenced Ethereum's decentralization and stressed that Ethereum should not be classified as a security.

This concept of sufficient decentralization means that the value of an asset is determined by the uncoordinated efforts of a wide range of people, rather than by a single, centralized or identifiable entity. The SEC's FinHub Framework document released in April 2019 introduces the concept of "active participants" to provide guidance for assessing reliance on the efforts of others. The idea is that a digital asset that was once classified as an investment contract may later be deemed a non-security if the efforts of the active participants diminish over time. This implies that the final requirement of the Howey Test is not satisfied because the promoters of the business cannot be identified, leading to the conclusion that an investment contract is deemed not to exist.

Part 2. Security Status of Staking Services

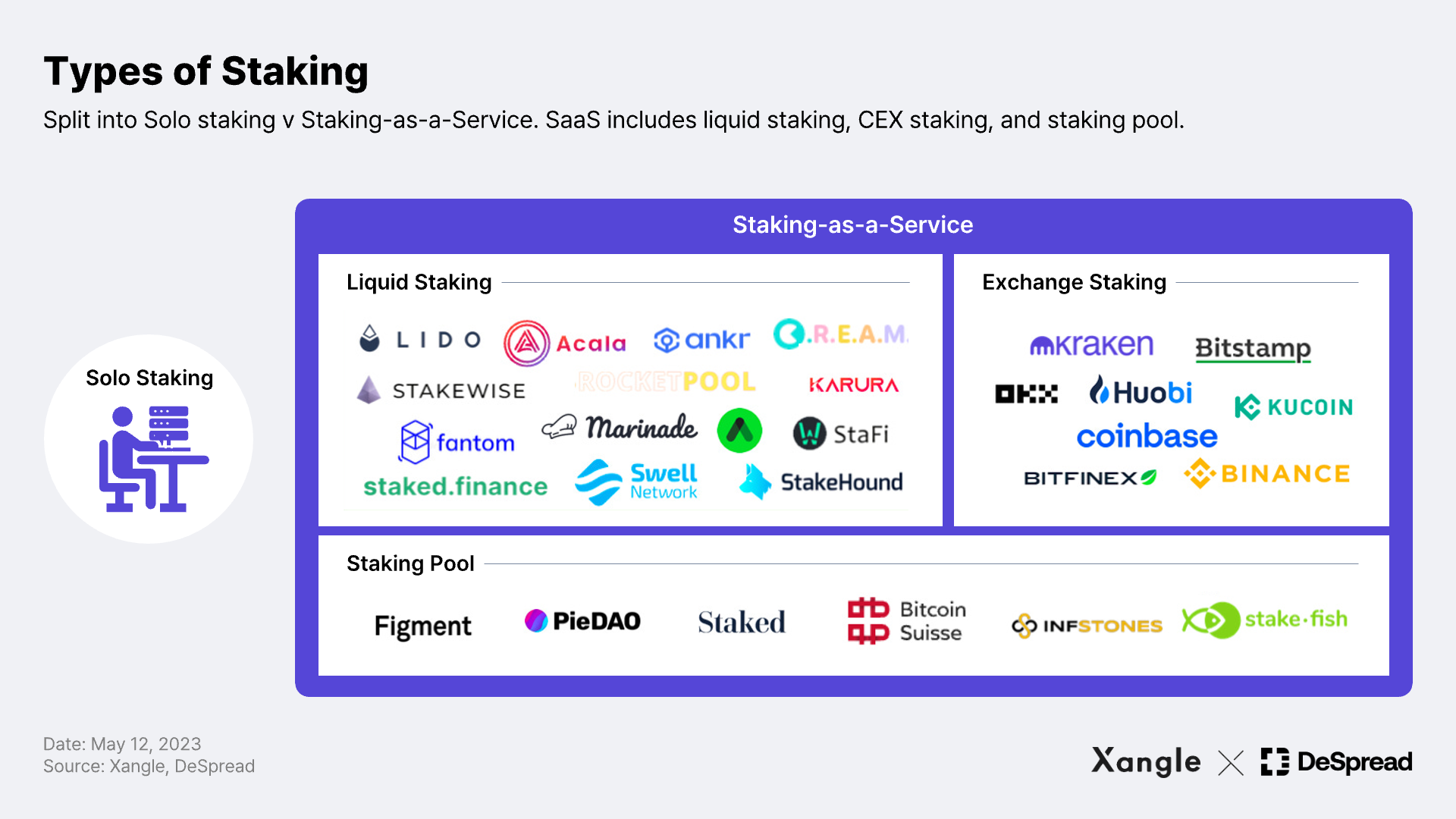

So far, we've explored the Howey Test and their supporting theories to discuss pros and cons about the security classification of staking under assumption of a 1:1 relationship between validators and the network. But as most staker don't have the infrastructure or technical knowledge to stake on their own, they turn to various Staking-as-a-Service (SaaS)* protocols based on the revenue stream of staking rewards, prompting questions whether staking services are securities.

*Staking-as-a-Service: SaaS is a service that revolves around staking rewards and asset delegation. It allows users to delegate their assets to validator operators who, in turn, provide a predetermined rate of rewards. The service comes in various forms, e.g., decentralized liquid staking platforms built upon protocols and decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs); as well as exchange staking, where exchanges enter agreements to manage client assets, operate the funds, and distribute returns in turn.

Types of Staking Service & Security Classification

There are many different forms of SaaS. The most prevalent types are 1) solo staking, where an investor directly runs a validator node; 2) exchange staking, where ownership of assets is delegated to an exchange for staking; 3) staking pools, where a specific entity collects funds for staking purposes; and 4) liquid staking, where assets are deposited into a contract within a decentralized protocol, and users receive staked representative tokens as proof of their stakes.

Here, the presence of an investment contract depends on how each service is actually implemented. To illustrate, let’s assume Ethereum ($ETH) is not explicitly a security. If an owner entrusts all the rights of $ETH to a staking operator and, in return, receives $xxETH tokens as proof of their stakes and profits from staking, the issued xxETH could be considered a security. This is because the profits earned from Ethereum staking are solely dependent on the efforts of others and the tokens are issued as beneficiary certificates that can be traded in the secondary market. Therefore, the degree of the security status may vary depending on how staking is performed and implemented.

Solo Staking

Solo staking can be viewed as an act of a staker enhancing the security of a network by providing their own capital, technical infrastructure, and labor to operate a validator node. Many argue that it does not pass the Howey Test because it does not form a collective group or depend on the efforts of others for its rewards, nor does it issue tokens that can be traded in the secondary market*. In particular, in the case of a sufficiently decentralized blockchain** like Ethereum, it is even more difficult to assert the existence of a specific entity acting as a promoter on behalf of the stakers and network participants, providing further justification for the prevailing view that solo staking does not constitute an investment contract.

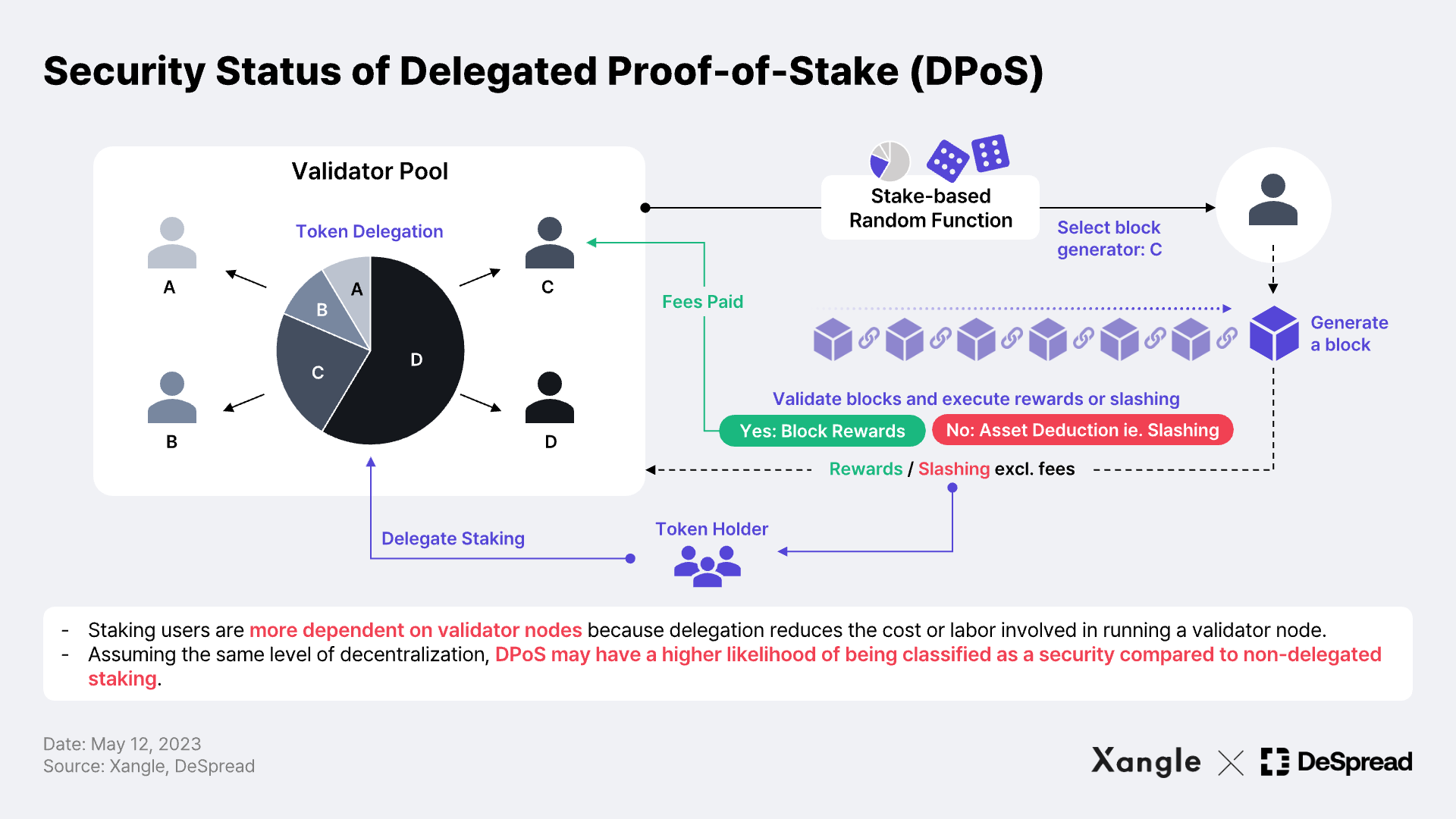

However, this view only holds true if there is a cost or effort involved in staking solo. Staking on a blockchain that uses a consensus algorithm with a built-in delegation mechanism, such as DPoS (described below) relies more on the efforts of the delegate compared to traditional PoS, increasing the possibility of security classification.

*Once issued, a token tradable on the secondary market may have the potential for arbitrage, thereby increasing the likelihood of passing the "expectation of profit" requirement under the Howey Test.

**This assumes a PoS blockchain where no specific person or entity has control over the assets on the chain. In this case, there should be a sufficiently decentralized network of validators and no excessive allocation of tokens to foundations or specific entities. The Nakamoto coefficient is one of the most widely accepted quantified decentralization metrics.

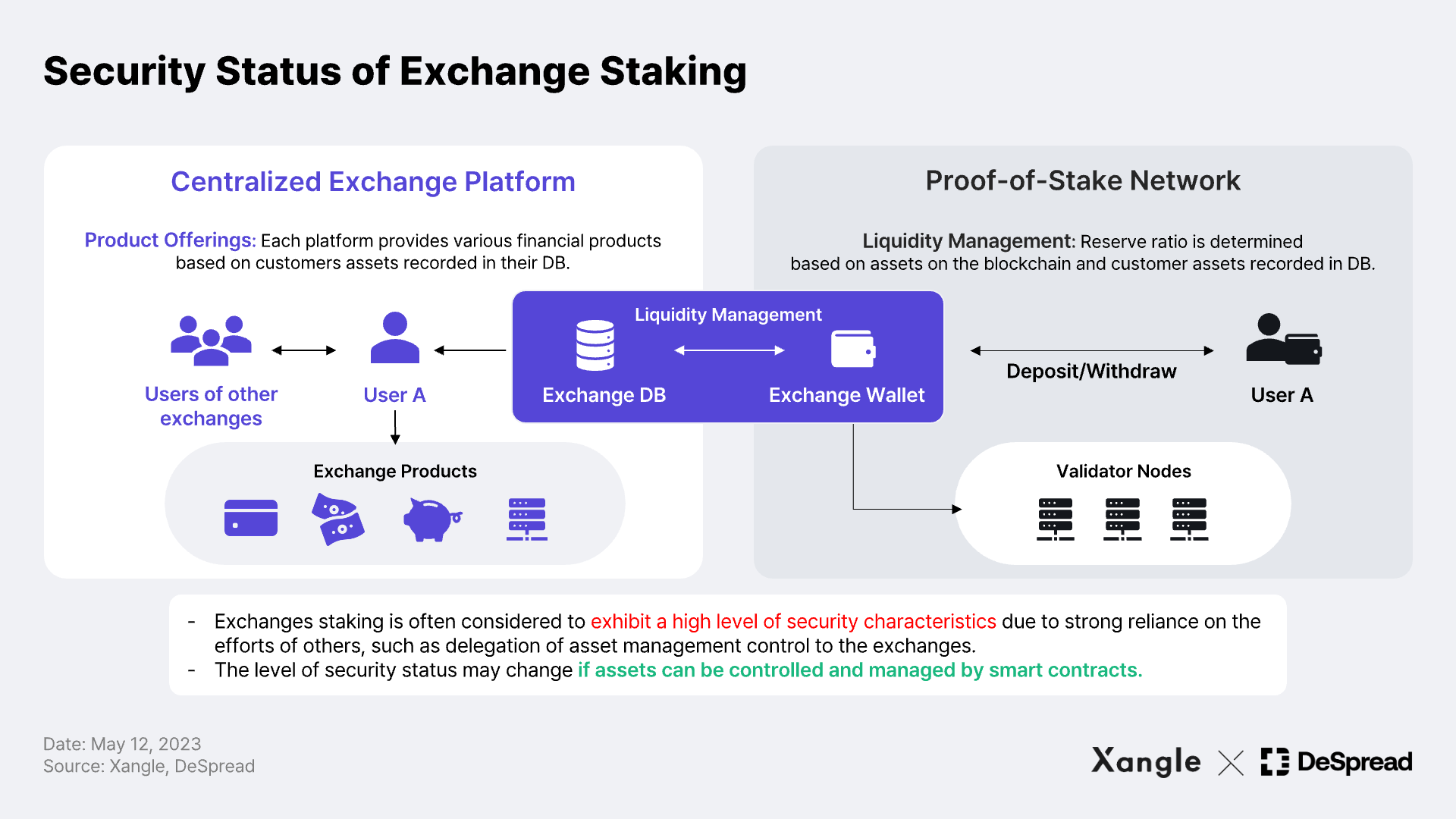

Exchange Staking

Exchange staking services provide an easy interface for exchange customers to earn staking rewards. The process of how and how much the exchanges are actually staking with customer assets is not fully transparent*, and the exchanges have de facto control over the assets. That is, exchange staking is generally regarded as less transparent and more custodial than on-chain staking services. Because of this, staking through exchanges is often considered more likely to be classified as a security compared to other types of staking.

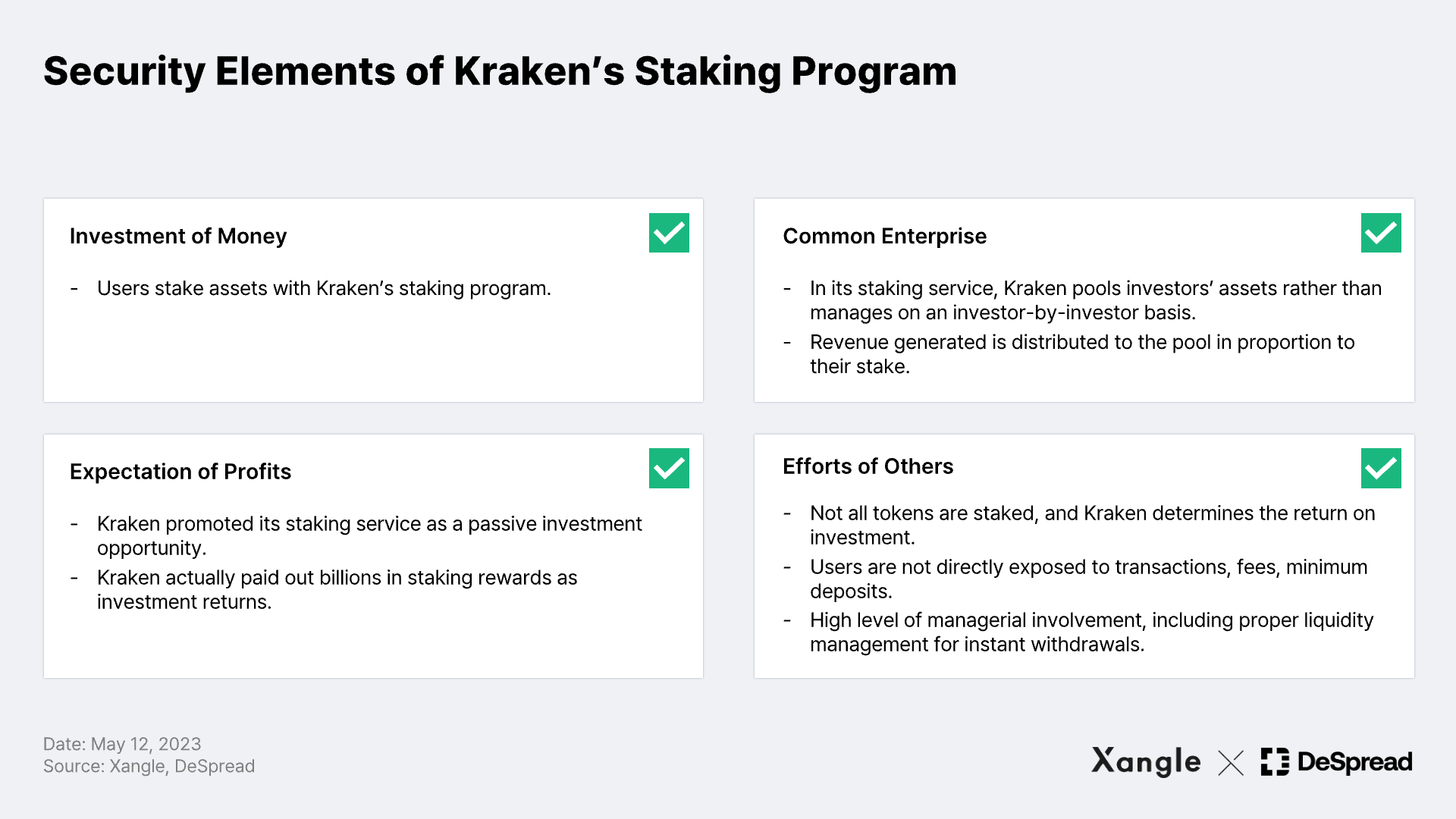

In addition, exchanges may maintain only a modest reserve requirement** for staking withdrawals, allowing them to allocate more funds towards higher yielding products or opportunities while not staking the entirety of the customer assets. This practice may result in information asymmetries, which have frequently been the epicenter of investor harm. An example of a company being accused of selling unregistered securities on this basis was the SEC's complaint against Kraken in November last year, which resulted in discontinuation of Kraken’s staking services in the U.S. and $35 million settlement. At the time, the SEC's complaint cited the following reasons in making such decision.

Yet, the determination of the security status may still hinge on how each exchange implements their staking services. Take Coinbase's Ethereum staking service as an example, which allows users to view user wallet addresses and staking transactions. Some argue that, in this case, the non-custodial and transparent nature of the service makes it less of a security than typical exchange staking services and more of a liquid staking.

In addition, in the case of staking services provided by large exchanges—whether it is simply an intermediary service that connects staking operators, or a proxy agent’s service that is inherently characterized as securities due to the faithful performance of fiduciary duties*—the security classification may still be determined by the manner the services are carried out.

*Most exchange staking services utilize customers’ crypto assets recorded in their DBs for staking on the blockchain network at the request of the customer. This creates data asymmetry between the exchange DB and the blockchain where the actual staking takes place. In particular, if the exchanges manage a large number of customer wallet addresses in the form of internally assigned CIDs (Customer IDs), known as exchange hot wallets, only the deposits and withdrawals of hot wallets operated by the exchange on each blockchain need to be processed, opening up risks of damage to investors caused by information asymmetry, most notably trading against customers leveraging records on the exchange DB.

**Reserve Ratio: Typically, reserve ratio indicates the percentage of deposits that banks are required to keep with the central bank, relative to the deposits they receive from customers. In the case of crypto exchanges, the reserve ratio refers to the proportion of reserves held in corresponding cryptocurrencies to address specific services or customer withdrawal requests.

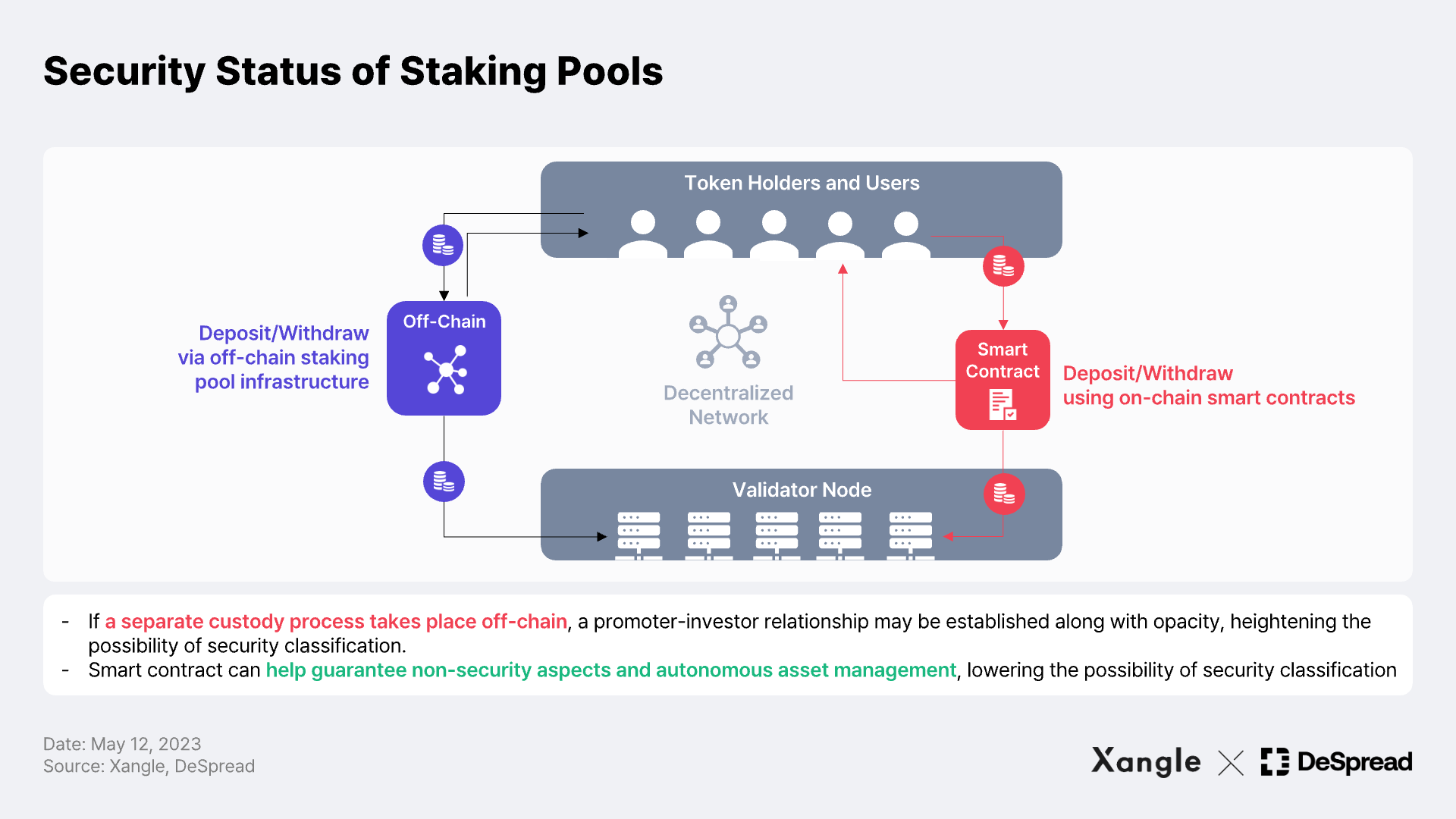

Staking Pools

A staking pool* is a service where the pool operator combines and uses assets deposited by investors to act as validators and distributes staking rewards to participants. As with exchange staking, information opacity and asymmetry often arise, and a promoter-investor relationship may be established between the pool operator and investors, raising possibility of its security nature.

Yet, the staking service of a staking pool operated in the form of a smart contract may not be an investment contract. This is because investors are guaranteed autonomy in managing their assets through deposit and asset management based on smart contracts, which enforce execution and fulfillment. Stakefish is a good example. In Stakefish’s staking service, the assets deposited by users are distributed to validators and used for validation, but all transactions are visible and deposits and withdrawals are freely available.

*Staking Pool: For the purpose of separation from the liquid staking protocols discussed later, this article is limited to staking pools where the operating entity is clearly defined and, in particular, no tokens are issued for secondary trading. Major players include Stakefish, Blockdaemon, Chorus One, Figment, PieDAO, and Bitcoin Suisse, with a wide spectrum of users.

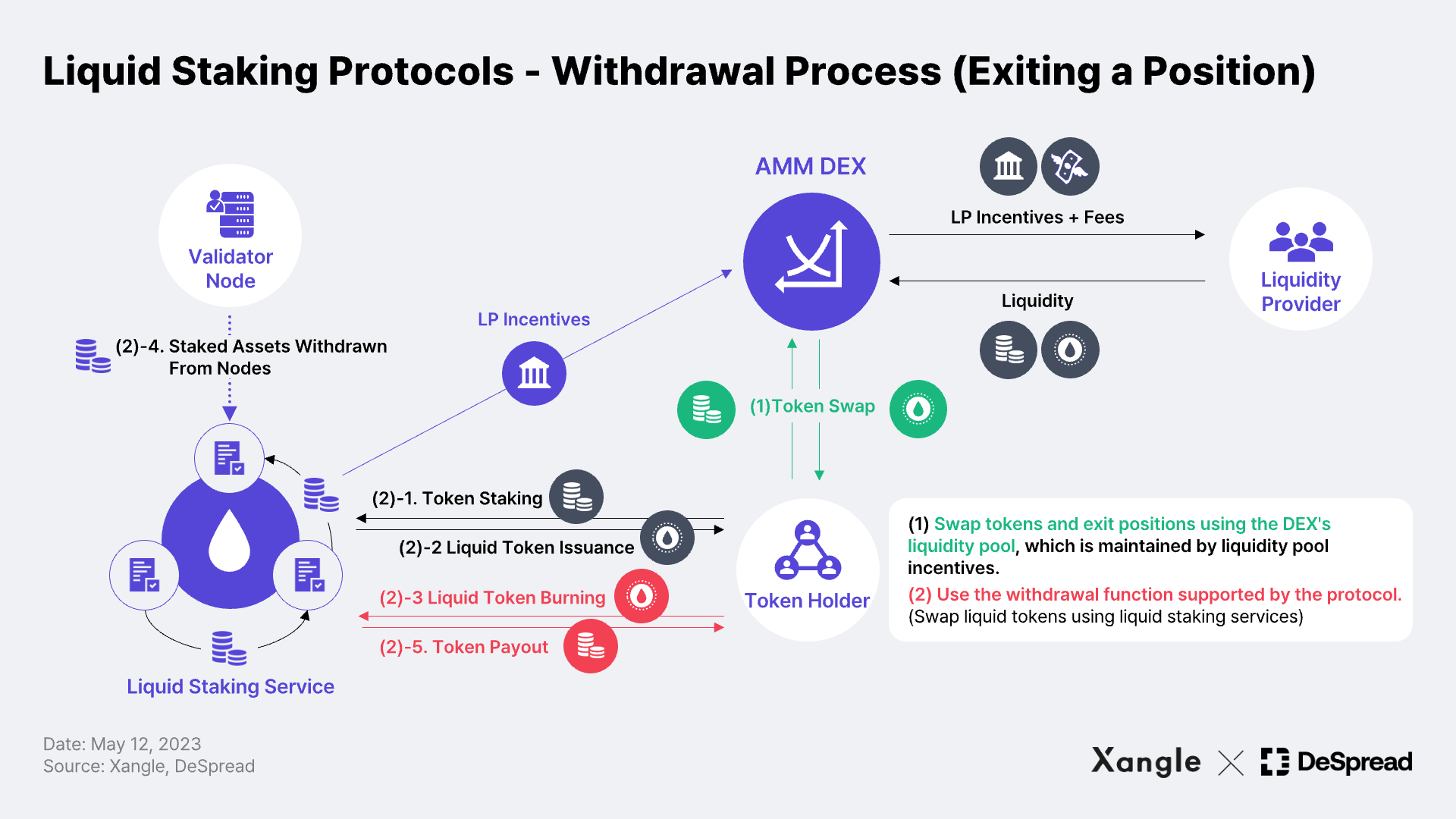

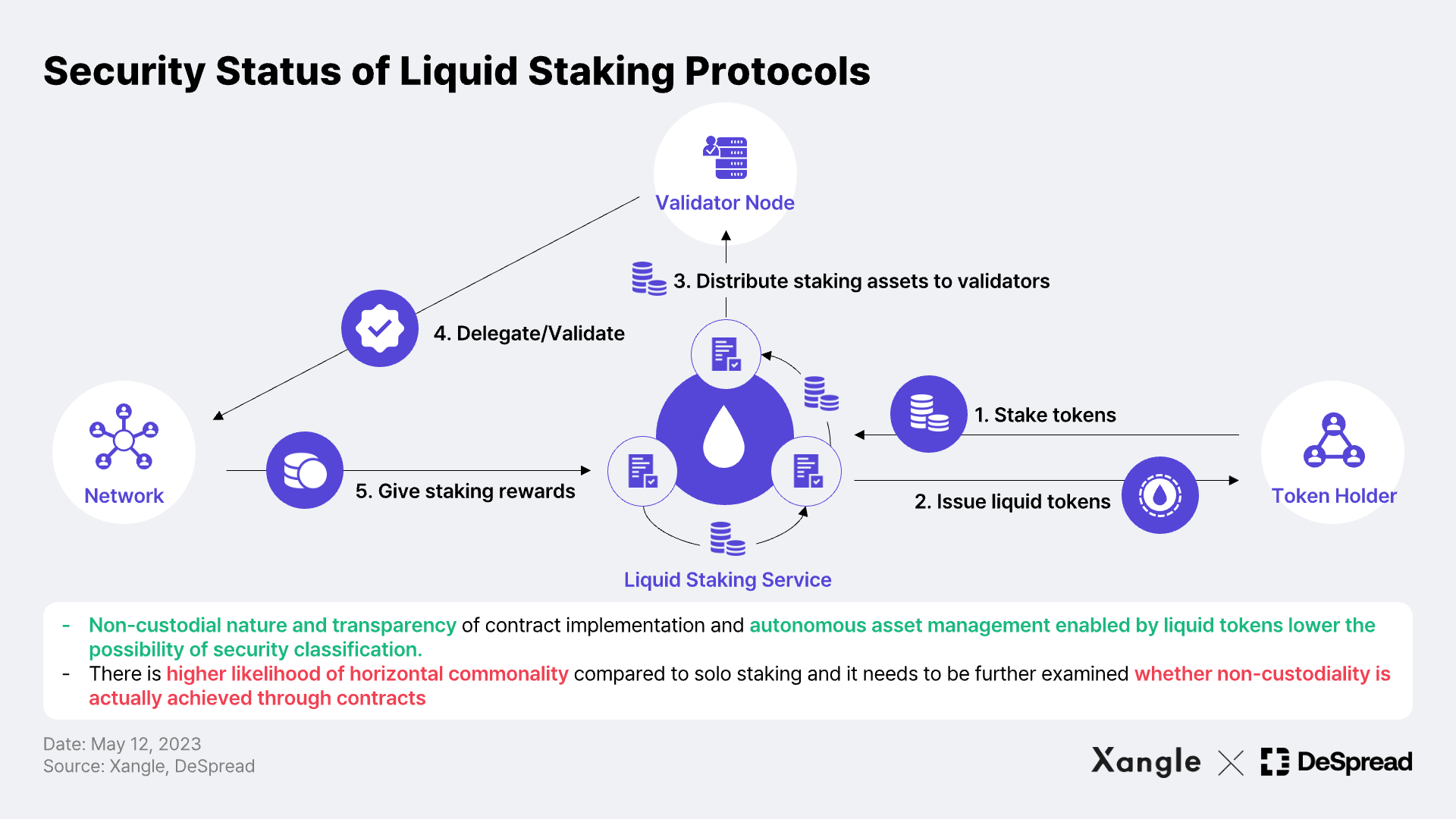

Liquid Staking Protocols

Finally, liquid staking* is a type of staking pool, which refers to protocols that allow users to deposit assets into a contract and issue liquid staking tokens to offset illiquidity risks of an asset. The non-custodial nature and transparency inherent in the use of smart contracts allow users to transact directly with the contract through their personal wallets, swap or unstake the issued liquid staking tokens, and manage their assets and positions at their discretion (see image below). The general consensus is that the majority of operators being decentralized makes the applicability of security classification less likely**. Here, I would like to put forth a few counter-arguments, as identifying securities traits requires a further examination of implementation and operation aspects of the protocols.

Firstly, commonality is more likely to be established in liquid staking than in solo staking. With a liquid staking protocol, there is a common purpose to increase the utilization of the protocol's governance tokens that are being distributed. Therefore, a co-operative relationship rather than a competitive relationship may be formed between pool participants, resulting in horizontal commonality***, and if the pooling of assets and the management of the resulting assets is included, horizontal commonality between investors and an investor-promoter relationship may be established, which may not be free from securities.

Furthermore, the non-fiduciary nature mentioned is not an absolute exemption in all cases. In situations where the user of a liquid staking service loses control over the assets, such as when the withdrawal period is so long that it is virtually impossible to withdraw at will, or when the service is operated by a single node operator, effectively delegating the assets to a specific possible entity, the staking service and the tokens issued may be classified as an investment contract.

*Staking is a high barrier to entry for individuals, as it requires development infrastructure, operation, and minimum staking amount to validate blocks on the network. Therefore, those who have staked assets but cannot afford the rest use liquid staking (see Xangle's Exploring Liquid Staking: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding the Concept), where assets are deposited into smart contracts that subsequently distribute the deposited assets to a group of validators. Especially since the Shanghai upgrade, various protocols, including Lido ($LDO), Rocket Pool ($RPL), and Frax Finance ($FXS), have gained significant traction (see Xangle's Liquid Staking Competition Set to Heat Up After Shanghai Update).

**As if to back this up, the liquid staking segment rallied and hit a series of new highs when the SEC's complaint against Kraken and the subsequent settlement were made public in November, as the market predicted that the flow of staking demand would converge on liquid staking protocols.

***The higher the percentage of a particular group's staked assets relative to the total staked in a Proof of Stake network, the greater the expectation of rewards for the specific group. In a PoS network, the higher the percentage of total staked assets in a given staking pool, the greater the likelihood of a block being generated, and hence the greater the reward per block. This is why staking pools may have a common purpose.

Other Factors: Tokens, Protocols, Decentralization, Transparency, and Non-Custodial Nature

Up to this point in the report, the arguments regarding the security classification of staking have primarily revolved around the implementation of the services. However, since staked tokens are cryptocurrencies before being used as a means of staking, there are several other factors that can influence the security classification besides the implementation and operational aspects of staking. In the following sections, we’ll take a look at the impact of the SEC's original sin and embodiment theories, decentralization, protocol design, and other key factors that are commonly relevant in determining the security classification of cryptocurrencies.

Tokens & Sources of Funding

Firstly, token issuance has the potential to move a staking service* further towards an investment contract. In particular, tokens that promise profits and the right to a stake in a staking pool may exhibit the characteristics of traditional securities, such as beneficiary securities and equity securities. Moreover, the tokens issued by staking services may expose retail investors, the top priority for protection, to secondary trading once they are distributed to an unspecified number of people through DEXs and lending protocols. In accordance with the priority of investor protection, issuance of tokens increases the likelihood that staking services may be defined as investment contracts.

In addition, under the aforementioned original sin theory, the SEC presumes that the sale of cryptocurrencies through an initial coin offering (ICO) constitutes a security. Therefore, raising funds to issue liquid staking tokens through an arrangement that has the characteristics of an investment contract, such as an ICO, could increase the applicability of security classification to all subsequent transactions, regardless of the circumstances or future developments.

*Staking rewards are accumulated within the staking pool of staking or SaaS operators. Since liquid staking tokens represent a stake in that staking pool, they also represent rights to revenue and withdrawal. Most liquid tokens (e.g., $rETH, $sfrxETH) follow the specifications of the **ERC-4626 Tokenized Vault Standard, and the staking rewards are accumulated in the token vault. The revenue is distributed in such a way that the exchange rate of a stake is increased when liquid tokens are swapped and burned.

Level of Decentralization

Decentralization is a key consideration in determining the security status of a cryptocurrency and is closely related to the fourth element of the Howey Test. For the sake of illustration, let's assume that the network is fully decentralized, in which no single entity can claim to be a promoter of staking rewards, but rather the network operates and develops based on the collective efforts of participants and is not dependent on the efforts of any particular third party. Therefore, higher levels of decentralization within a staking-based network have the potential to reduce the likelihood of security classification.

The SEC's view is no different. A prime example is Former SEC director Hinman's speech in which he stated that Ether, which was previously classified as a security through the original sin theory, was reclassified as a non-security based on the embodiment theory and sufficient decentralization. Another example is Stacks ($STX). Stacks was the first to hold a token sale under SEC Regulation A+ in 2019 under the name Blockstack*. It has since split into several foundations and research and development teams, including Hiro, to allow for independent decision-making by each participant. In 2021, the company announced that it filed its last annual report with the SEC, arguing that the protocol is sufficiently decentralized.

Finally, because decentralization is a prerequisite** for characteristics of PoS blockchains, i.e., non-custodial nature, trustlessness, and transparency, low decentralization of a blockchain network may increase the potential of security classification across the board by diluting the notion of a distributed public ledger fundamental to blockchain. For this reason, achieving a high level of decentralization is widely regarded as the surest way to reduce the possibility of security classification.

*In 2019, the Blockstack PBC, which leads the Stacks project, conducted a public sale of tokens under Regulation A+ of the Securities Act. This involved the sale of STX tokens, which were considered securities at the time, making it the first public token sale recognized by the U.S. SEC.

As the Stacks network matured and became more decentralized, the classification of the STX token was significantly challenged. In January 2021, it transitioned to the fully decentralized Stacks 2.0 blockchain, where no single entity, including the Blockstack PBC (later rebranded as the Hiro Systems PBC), controls the development or operation of the network. At the time, Hiro Systems PBC argued that it did not meet the conditions of the Howey Test, noting that more than 40 miners and 1000 nodes had gone active on the network since the launch of 2.0 and that the Stacks blockchain had no management team.

Some argue that STX no longer meets the definition of a security under U.S. law, citing such developments and the SEC's framework for investment contract analysis for digital assets. The main rationale behind this conclusion is that the network is sufficiently decentralized, there is no longer a single group responsible for the success or failure of the project, and STX token holders can earn profits without relying on the efforts of others.

**Protocol security of PoS blockchains: PoS features, such as immutability, transparency, and non-custody, are predicated on the decentralized distribution of staked assets. In a PoS setting, a single entity that owns enough stakes to intervene in the process of block generation and consensus can not only destroy the cryptoeconomic security but effectively disable the aforementioned qualities.

Protocol Design

Staking can also be judged differently depending on the protocol design. For example, consider delegated staking in Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS). Except that users are rewarded with tokens for contributing to the security of the protocol, delegated staking incurs less cost or labor to run a validator node. In this case, the return may become heavily dependent on the efficiency* of the validator nodes to which staking assets are delegated. Assuming equal decentralization, DPoS staking has a higher potential to be classified as securities than staking without delegation.

*Performance of validator nodes: The operators of validator nodes run the technical infrastructure to power the blockchain's peer-to-peer network. There are various metrics to gauge the performance of infrastructure operation. They include uptime, block proposal rate, slashing, staked token balance, software/hardware performance, and governance participation, which collectively determine staking rewards.

Transparency

While the primary objective of securities laws is to protect investors, much of the financial harm arises from investor-promoter information asymmetry. In this context, actively and transparently communicating with investors in an attempt to address such information asymmetry can be a positive for project’s autonomy. This can be achieved by making the project's contract code, whitepapers, and developer documentation publicly available. Further, providing accessible materials that can be understood by a broad range of people, including retail investors, can lower the likelihood of security classification, as it reduces the necessity of separate disclosures.

*Though greater transparency does not guarantee immunity from security classification, it may still contribute to non-security status. A relevant case is TurnKey Jet, Inc. The SEC's Division of Corporation Finance issued a "no-action letter" to the company, which asked whether the TKJ tokens issued by TurnKey Jet constituted securities under the Securities Act. The SEC's "no-action letter" indicated that the SEC did not intend to bring administrative proceedings against TKJ tokens for alleged unregistered securities sales. The "no-action letter" is believed to have based itself on the grounds that: 1) Turnkey Jet used the sales proceeds for operation of the platform, not for speculative purposes, and 2) the token purchasers were informed of the terms and conditions of the TKJ token through sufficient disclosures.

Control

Finally, control over the deposited assets is key to determining the security status of staking. In particular, the lack of control over the withdrawal and deposit of assets regarding the fourth element of the Howey Test (Solely* from the efforts of others) strengthens the case for security classification as it may suggest the presence of vertical commonality between the promoter and investor.

A pertinent illustration is Senator Cynthia Lummis' remarks on Ethereum's post-Merge environment. Senator Lummis, who is also known as the proposer of Wyoming's DAO legislation, commented on Ethereum's transition to PoS that "there's room for it to be seen as a security because it's not immediately possible to unstake the tokens."** What triggered her comment was the absence of control over the staked tokens. This, combined with other precedents that emphasize the significance of control, serves to highlight the critical role control plays in determining the security status. Consequently, the extent of control a staking service grants to users over the deposited assets becomes a key determinant. If a staking service provides non-custodial services (e.g., use of smart contracts), users are given control over the assets, including deposits, withdrawals, and swaps, potentially diminishing the security characteristics of the staking service.

*Solely ⇒ In SEC v. Glenn W. Turner Enterprises, Inc. 474 F.2d 476, 482 (Ninth Cir. 1973), the term 'solely' was replaced by 'significantly' to discourage the practice of involving investors in operations as a means to evade the definition of a security.

**On December 7, 2022, Cynthia Lummis stated on the “All About Bitcoin” program, “It’s a security because of the way [it] moved from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake, inability to [unstake tokens] right now makes it susceptible to being [considered] a security.”

***Cases holding that control is material to security classification include Steinhardt Group, Inc. v. Citicorp, 126 F.3d 144, 152 (3rd Cir. 1997) and Robinson v. Glynn, 349 F.3d 166 (4th Cir. 2003). In each case, the court acknowledged the significance of control, stating that “due to limited partner’s ‘pervasive control over its investment in the limited partnership,’ no investment contract is present” and “interests in limited liability company deemed not an investment contract due to investor’s active managerial input.”

Closing Thoughts: Barrage of Regulations Clouding the Outlook for Crypto

Staking: Traversing the Enigma of Uncertainty

An In-depth Look at the Regulatory Landscape of Staking

This report zoomed in on key discourses surrounding staking. In the first half of our discussion, we looked at how the SEC and the Howey Test came into being, explored why staking might pass the Howey Test along with the original sin and embodiment theories that support the SEC’s position. We then went on to explore the opposing viewpoints on the other side of the aisle why it might not pass the Howey Test, highlighting the significance of economic realities and sufficient decentralization. In the latter half, we looked at how security status may occur in Staking-as-a-Service, which is deemed to go beyond solo staking on several fronts. Finally, we dedicated the last section to discussing the main factors that could lead to the classification of cryptocurrencies as securities, aside from staking activities.

Domestic Implications; Uncertainty Nearing Its End

Although South Korea's Capital Markets Act is said to be less “comprehensive”* than the U.S. securities laws, the SEC's determination is expected to have a far-reaching implications in the country. The category of investment contract securities, newly created in 2016, resembles the “comprehensive” nature of the U.S. securities laws, which apply general principles to non-standard securities. In particular, the criteria of security classification of cryptocurrencies have gained exceptional importance, as the resulting conclusion will guide the subsequent actions following the LUNA/UST crash on May 9, 2022. Since $LUNA is the native staking token of the chain before being collateral for $UST, the SEC's remarks and future policies will likely serve as a barometer for South Korea’s crypto industry in terms of security classification.

On a positive note, there are signs that this uncertainty is being resolved. In April, Coinbase won a lawsuit against the SEC seeking clearer regulatory guidance. The ruling puts the SEC in the position of having to provide specific security classification guidelines in the near future. Coupled with this, a closure to Ripple and the SEC's court battle that are expected to arrive in the next two to six months, will further lower the uncertainty.

* South Korea's Capital Markets Act mentions "stakes in indirect investment vehicles using "associations under civil law and undisclosed associations under commercial law" as new types of securities permitted by the introduction of investment contract securities. These examples leave room for the interpretation that investment contract securities are actually regarded as a “specific type” of securities in the Capital Markets Act, as opposed to Howey's generalized definition of investment contracts as securities. If this is the case, then broad applicability in Capital Markets Act is in fact very limited. - Kim, J. B. (2018). Is Bitcoin a Security? Defining Securities and Protecting Investors. Securities Law Review, 19(2), 171-198.

Long Live Crypto

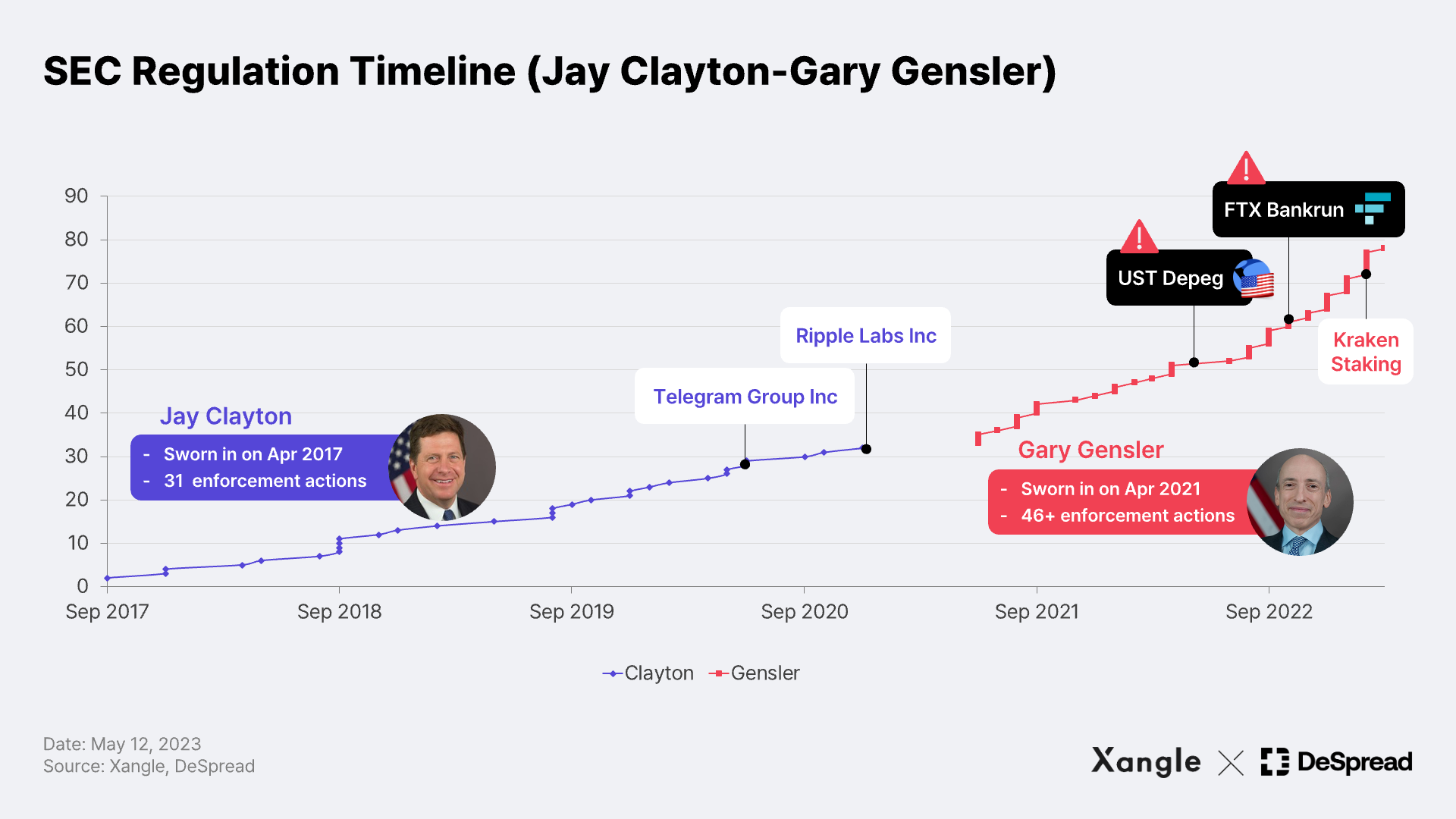

ICOs During Jay Clayton's Tenure

In fact, this is not the first time the SEC has taken on the crypto and digital assets market. Under Jay Clayton* as Chair of the SEC, the SEC brought more than 27 lawsuits and enforcement actions against the then-popular Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), starting with Ethereum's crowdfunding platform, The DAO**, in 2017. A series of such actions succeeded in bringing the practice into the category of investment contracts, cementing the original sin theory as a fundamental concept for regulating cryptocurrencies.

But despite these ICO regulations, blockchain and the applications that build on it have grown by leaps and bounds, uncovering new sectors like DeFi and NFTs and their value. Advances in blockchain technology, i.e., ZK rollup, danksharding, and new consensus algorithms have revolutionized the cost of trust associated with public distributed ledgers since. Despite the near-term uncertainty surrounding the definition of investor interests, the evolution of regulations is expected to facilitate the growth of the cryptocurrency market.

*Jay Clayton was appointed by former U.S. President Donald Trump and served as chair of the SEC from May 2017 to December 2020.

**The DAO is a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) based crowdfunding platform launched on Ethereum in 2016 that raised $150M. Shortly after the launch, however, over $50M was stolen during a re-entrancy attack. The Ethereum community was divided on measures to be taken in the aftermath, and the ensuing debate over soft fork and hard fork led to the creation of Ethereum Classic ($ETC) and the current Ethereum.